Bede's Letter to Plegwin

Some of you might vaguely recall I had started a series about a year ago on biblical chronology. It started with a commentary on some research into human lifespans and continued with an overview of questions about biblical chronology and a discussion of William Henry Green's influential article, and concluded with a commentary on arguments from incredulity. I hadn't intended to just drop the subject, but you know how this year's been. First, I was in a movie, and then we had a busy summer with conferences, and then we bought and renovated a building! I never stopped thinking about the subject though, and now I wanted to post a few comments on Bede's Letter to Plegwin.

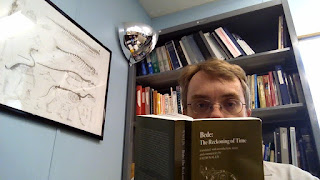

Say what? Okay, a little background is in order. The Venerable Bede was an English monk who lived in a monastery way up in the northeastern part of England (Tyne and Wear) back in the eighth century. He was a really important English author who, according to Wikipedia, "made the Latin and Greek writings of the early Church Fathers much more accessible to his fellow Anglo-Saxons, which contributed significantly to English Christianity." Core Academy has a copy of his commentary on Genesis, and I just snatched up a copy of Faith Wallis's translation of Bede's The Reckoning of Time (see above).

Reckoning of Time turned out to be far more complicated and fascinating than I expected. The basic problem was determining the date of Easter, and Bede wrote this book to explain how this was done. I've never really given this a lot of thought, since someone has always been around to tell me the date of Easter, but it was a big deal in the early church.

The basic problem is that the lunar cycle (which gives us our months) doesn't match up perfectly to the solar cycle (which gives us our years). Since we know Jesus died and rose again at Passover, celebrating the resurrection should coincide with the Passover. But the Bible describes the Passover as a day of the first Jewish month, which then has to be correlated to the solar year. Since the lunar year and solar year don't match, you have to figure out when to add extra days (and even months) to the calendar to make the scheme work out. Bede's Reckoning of Time is like a textbook explaining how this whole process works. I was deeply impressed with the ingenuity of these early calendar calculators.

And what does this have to do with the date of creation? Bede's Reckoning includes a section called "The Six Ages of this world," which is basically a historical chronicle from the beginning of time. In creating this chronicle, he relied on dates calculated from what we know as the Masoretic text. As I wrote previously,

We have three basic manuscript "versions" of the Old Testament: The Masoretic, the Septuagint, and the Samaritan. The Masoretic is the one that Protestants use today to translate the Old Testament. The Septuagint is an ancient Greek translation, and the Samaritan was an independent Hebrew version of the Old Testament preserved in the city of Samaria (the old capital of the northern ten tribes of Israel). They are mostly the same and definitely tell the same stories, but there are some differences. One of those differences is the ages of the patriarchs. If you add up the ages of the Masoretic, you get 1656 years between creation and the Flood. The Septuagint records 2244 years, and the Samaritan 1307.Using the Masoretic numbers, Bede placed the birth of Christ 3,952 years after Adam, but he acknowledged that those who used the Septuagint calculated 5,199 years between creation and the birth of Jesus.

That brings us to the Letter to Plegwin, which Bede wrote to defend himself against a charge of heresy. We don't know much about Plegwin, except that he was associated with Bede's bishop, Wilfred. At dinner with the bishop one evening, an unidentified "lewd rustic" had accused Bede of heresy because he put birth of Jesus in 3,952 rather than 5,199. That allegedly moved Jesus' birth from the beginning of the Sixth Age of the world to the Fourth Age. Bede only found out about the accusation later.

Let me begin by acknowledging that I was troubled that Christians were once so hung up on this chronology that they actually considered questioning it to be heresy. Heresy is denying the person and work of Christ. Questioning peripherals like chronology cannot be heresy. It's not a gospel issue.

The Letter to Plegwin is a nice little summary of Christian thought on the Masoretic vs. Septuagint ages. Bede prefers the Masoretic dates, which he refers to as the "Hebrew Truth," because he thinks this is the original language. He never discusses why the numbers of the Septuagint were "wrong," but he does quote Augustine and Jerome on the subject, who agree with Bede that the Septuagint's numbers are incorrect.

So why would anyone think the Septuagint chronology would be authoritative? Well, here's where it gets weird. Jerome selected the Masoretic dates to include in the Vulgate, so the Bible available to Bede supported the shorter chronology. But another important source for historical information was the early church historian Eusebius, who wrote from Greek sources. His chronology was derived largely from the Septuagint.

So Eusebius' history had become revered with its chronology that disagreed with the chronology that could be calculated from the Vulgate! Does that make for a charge of heresy for choosing one over the other? I don't think so. Bede didn't think so either, especially when he sided with Augustine, Jerome, and the Vulgate itself.

If you have an interest in this, Bede's Letter to Plegwin is an interesting place to start to learn about ancient opinions about the Septuagint and chronology. You'll find it in the appendix of Bede: The Reckoning of Time.

Feedback? Email me at toddcharleswood [at] gmail [dot] com. If you enjoyed this article, please consider a contribution to Core Academy of Science. Thank you.